Ever since the year 1810 the Yorkshire and Lancashire people have been peacefully struggling for Universal Suffrage. […] You have no idea of the intensity of radical opinions here – you have an index from the numerous public house signs – full length portraits of [Henry] Hunt – holding in his hand scrawls containing the words Universal Suffrage, Annual Parliament, and the ballot. Paine and Cobbett also figure occasionally.[1]

-Henry Vincent in a letter to his brother, 1838.

Pub politics is by no means a recent phenomena. While over the last year Leeds has seen various demos ending in pubs, their band rooms frequent haunts for student societies, the act of politicising the public house has a long and rich history. Previous scholars, including Brian Harrison in his seminal Drink and the Victorians, explored how the public house was indeed the heart of the community long before the nineteenth century and a source of safe water and drink in urban areas, while AnneMarie McAllister is currently producing some very interesting and relevant work on the peaks and troughs of temperance movements in Britain. That said, when I came to research representations of the pub in the literature of the Chartist movement, I was grasping for (ahem) straws.

Katrina Navickas’ recent book (and accompanying web project) explores the tradition and contestation of Radical politics in the public house: noting that the public house was both the centre of local communities and often the only public space available for large meetings, as “public’ buildings in the inclusive sense of the term had hardly existed in northern English towns before the 1840s,” with many civil, commercial, and residential buildings and areas effectively ‘privatised’ by the ruling elite.[2] Indeed, she notes that Bradford magistrates would deliberate over trials in the pub until the Bradford courthouse was completed in 1834. [2]

Much in the same way that the pub is the home of casual chatter and student activism today, at the turn of the eighteenth century, “radical meetings in pubs drew from the same culture of self-help and autodidact activities that were common in such venues,” including circulating libraries for books and local newspapers.[3] Further to this, the pub occupies a liminal space between public and private; open to all, but its physically small size meant that meetings could be prioritised to only interested parties, away from eavesdroppers. While pubs were, and continue to be, very much community-defined, and not all pubs would be open to all, within working class communities during the early Victorian period it provided a space to express anti-establishment views without fear of persecution.

Today I will discuss the practicality of the pub with regards to the Chartist movement, and in particular what this meant within Leeds. Chartist leader and teetotaller Henry Vincent, in his letter above, notes that the north of England is unashamedly progressive in its politics, having campaigned for equal suffrage since the early 19th century, but also that the public house was central to this campaign. Emblematic figures of suffrage such as Chartist leader Henry Hunt (above), as well as progressive philosophers Thomas Paine and radical MP William Cobbett, literally take on the status of icons to represent the ‘house[s] of the public’ within Yorkshire.[4] These icons furthermore emphasise the power of literacy, noting the scrolls inscribed with the demands of the Charter, giving some indication of the intellectual activities taking place within the pub. During the early part of the Chartist movement, the pub was seen as a most practical place, and the ‘numerous’ pubs Vincent speaks of are no accident. In 1830 a peculiar piece of legislation entitled the Beer Act passed, which “allowed anyone to sell beer (but not wines or spirits) on the mere payment of an excise fee of two guineas,” in an attempt to curb the infamous ‘gin problem’ characterising poor industrial areas at the time.[5] While the Beer Act was unsuccessful in solving the gin problem, it did almost double the number of pubs opening before 1838. Warmer and drier than many Yorkshire residents’ cramped and damp residences, the pub was also a more statistically viable meeting place: with just under 200 heads per pub by 1838.

Figure 1

| Estimate population of Britain (rounded) [6] | Estimate no. of pubs and beer-shops (rounded)[7] | Estimate ratio of heads per pub in Britain. | |

| 1830 | 16,150,000 | 45,000 | 358 |

| 1838 | 17,800,000 | 90,500 | 196 |

While teetotallers couldn’t argue with the prevalence of pubs, price did prove to be a contentious issue. Many meeting rooms were hired free of charge for Chartist meetings, with the levy of a ‘wet rent,’ at the cost of a drink per person, fronted by the individual attendees.[8] At only a few pence for a mug of ale, this was considerably cheaper than hiring a civic hall but did lead to some debates about the proper use of disposable income, especially as wages fell and food prices rose during the 1840s. That said, it was a small price to pay for the physical and emotional warmth that this public space offered to its inhabitants at the time.

Many organised societies took advantage of these practical advantages too, whether explicitly political or not. Friendly societies provided benefits to their subscription paying members as a working class solution to middle class life insurance policies, including sick pay for members, and funeral expenses and pensions for the dependents of deceased members. Meetings of these organisations would be reported in newspapers like the Northern Star, emphasising the closeness and fraternity of the group in their invitation notices. In June 1838 the Leeds United Order of Oddfellows report the opening of a new lodge at the Woodman Inn, Leylands, which “promises fair to be a strong and powerful society,” and “beg distinctly to state that the order recognises no difference between Catholic and Protestant, Jew and Gentile. […] They take good men of all denominations, and so far as they can judge refuse bad ones.”[11] For the LUOO, the pub represents a secular centre for cultivating friendships without prejudice, where men can be united by their shared oath and find further welcome in aligning themselves with the pro-suffrage standpoint of the newspaper in which their reports appear to the world.

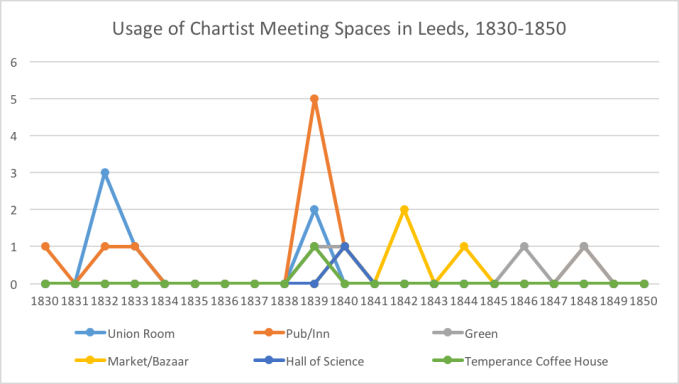

The use of the public house as a meeting space declined during the 1840s for a myriad of reasons, a link between the idea of ‘responsible economy’ of saving one’s precious wages for food, in addition to the necessity of performing respectability to the middle class legislators by shaking off the reputation of being dirty and drunk. This pattern holds true for Leeds, and we can see the expansion of the Chartists into commercial spaces including the ‘Chartist Room’ in the newly built Kirkgate Market. Katrina Navickas’ Protest Histories project contains a well-curated database of all radical meeting spaces in Leeds at this time, and I have taken her data and adapted it to show central Leeds during the period 1830-1850.

For a historical night out in Leeds, look no further! Spaces such as the Angel Inn remain functioning pubs, and remarkably much of Leeds City Centre has retained its original Victorian architecture. ‘Ginnels’ in the town centre including Angel Inn Yard and the narrow street of Central Road have merely been improved rather than redeveloped, and provide a great sense of spacial awareness and city planning experienced by the Chartists. The lasting legacy of pubs such as Whitelock’s and the Angel is cause for further historical speculation: how did these pubs remain, and in what ways did they retain their radical allegiances since the Chartists? Their steadfastness is especially interesting considering the drop off in usage of pubs over the 1840s, coinciding with the formation of one of the longest-running Temperance organisations, the Band of Hope, founded in 1847.[12]

Figure 2

Whatever political issue ails you, take a leaf from the Chartists – get out and talk about it.

For more information about suggested routes, accessibility, or more detail about specific Chartist meetings, get in touch.

One thought on “Before the Otley Run: A Chartist Pub Crawl of Leeds”